Falaknuma: an Indian palace is reborn

The home of the scandalous Nizams of Hyderabad is now a hotel.

IN THE GAMES ROOM

of the Taj Falaknuma Palace there is a photograph of the Sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, Mahboob Ali Khan, standing astride two magnificent tigers, shot dead by his rifle. The photo is somewhat less impressive when you learn that the tigers were bought from a dealer in Bombay, tied to a tree in the jungle and rubbed with laudanum to make them sleepy, so that the Nizam and his entourage, arriving by private railroad, could trap and kill them without risk. When you’re the Muslim ruler of India’s largest state and your riches outshine even those of the fabulously wealthy Indian princes, you’re allowed to cheat a little.

The tiger-hunting Sixth Nizam inherited an empire that stretched back to 1724, when his ancestor Nizam al-Mulk, as a reward for his loyalty to the Moghuls, was granted dominion over the vast southern plateau known as the Deccan, coveted for its rich deposits of diamonds, rich black soil and deep-water ports. Loyal in turn to the Moghuls and Indian’s British rulers, the Nizams were in fact not princes but viceroys and governors, growing wealthy from collecting rents and taxes from their prosperous subjects. By the nineteenth century, Hyderabad, the seat of the Nizam’s power, was the greatest cultural centre in India, blending Moghul, Persian, Hindu, Sikh, Parsi and Christian traditions.

Mahboob was only two years and eight months old when his father died – spoiled, wilful, and indolent, he grew up to be recklessly extravagant, hopelessly disorganised and rather too devoted to the bottle and opium pipe. Fond of schoolboy pranks, he once had a flock of live birds fly out of the crust of a pie he served to Lady Curzon, the wife of the British Viceroy.

FOND OF SCHOOLBOY PRANKS, HE ONCE HAD A FLOCK OF LIVE BIRDS FLY OUT OF THE CRUST OF A PIE HE SERVED TO LADY CURZON, WIFE OF THE BRITISH VICEROY

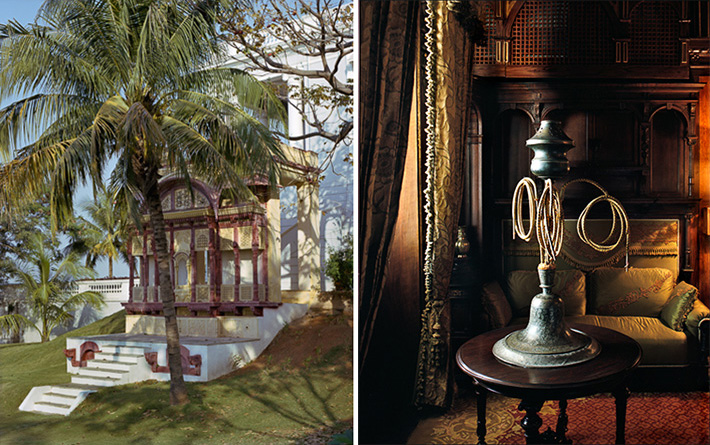

In 1895 Mahboob visited a former Prime Minister, Vicar ul-Umra, and remarked how much he liked the nobleman’s home, which was known as the ‘Palace Below the Heavens’ for its superb location high on a hill overlooking all of Hyderabad. According to tradition, Vicar ul-Umra was then obliged to ‘gift’ the palace to the Nizam. The Nizam and his family moved in the next day. The building of Falaknuma (meaning ‘sky lake’ or ‘mirror of heaven’) had taken nine years, almost bankrupting its owner. Undaunted, the Nizam then proceeded to spend the next 22 years decorating it, filling it with statues and priceless ornaments from every corner of the world, including 24 carat gold light fittings, embossed camel leather wall coverings, Bohemian chandeliers, French parquetry, British stained glass, Chinese silk furnishings, several thousand rare books, ornate clocks, eighteen types of Italian marble and the world’s most valuable private collection of jade. The palace boasted the longest dining table in the world, seating 101 people, a private telephone exchange and a zenana for uncounted hundreds of concubines. The result of such undisciplined accumulation of objects was an ostentatious mishmash of popular nineteenth and early twentieth century decorating styles, from Tudor revival to Art Deco.

Palace historian Prabhakar Mahindrakar first laid eyes on Falaknuma in 1995, when the Taj group took on the daunting task of restoring the property and turning it into a sumptuous hotel. Along with several of the Nizam’s palaces, it had been left to ruin. During the latter part of the 20th Century, fortunes had been squandered, palaces shuttered and treasures looted. The last person to stay there was the Indian Prime Minister in 1951. The palace grounds were covered with high grass and overtaken by wild dogs and snakes. The slums of Hyderabad had crept up the mountain and were encroaching on the palace walls. ‘There were huge cracks in the interior walls and water gushing through the ceiling,’ Prabhakar says. ‘I thought the whole building would collapse.’

How such a magnificent building fell into such disrepair is in a great part due to the lack of interest in it by Mahoob’s grandson, Osman Ali Khan, the Seventh Nizam, and his grandson, Mukkaram Jah, a restless soul who had little affection for Hyderabad or his exultant role as Eighth Nizam.

The Seventh Nizam was the richest man in the world in the 1930s and 1940s. His collection of pearls alone, it is said, could fill an Olympic sized swimming pool. And yet, he was notoriously frugal and dismissive of his wealth. He carelessly piled small mountains of diamonds by his bed, kept several thousand unopened cases of Moet & Chandon in his cellar and had enough cash lying around in forgotten places that it was snacked on by rats. He used the 400-carat Jacob Diamond as a paperweight. But when his walking stick broke he had it repaired with string. He knitted his own socks. And, despite having a fleet of Packards, Fiats and Rolls Royces, he drove around in an old 1934 Ford Tourer. At the end of his life, he had allocated himself a living allowance of just 7s 6d a week. He never lived at Falaknuma, disliking its ostentation. It became a guesthouse for dignitaries and no one lesser than a viceroy was permitted to stay there.

Osman passed the title to his grandson, Mukarram Jah, who was crowned Eighth Nizam in 1967. By then, it was purely ceremonial, as Osman had unwisely fought against the independence of India in 1947 and been stripped of his powers. Jah too barely spent time at Falaknuma. Educated at British military college Sandhurst and more interested in tinkering with trucks than living in palaces or dealing with squabbling heirs, Jah would eventually fall in love with half a million acres of outback near Geraldton, Western Australia, and turn his back on India to become, of all things, a sheep farmer. After four failed marriages and hopelessly inept at sorting out the legal and financial mess he inherited, Jah would eventually lose the sheep station too, and die in Turkey a virtual recluse.

Here Mukarram Jah’s ex-wife, Princess Esra, enters the picture. The Turkish beauty married Jah in 1957 when she was studying at the British Institute of Architecture and he was at Sandhurst. The marriage fell apart when Jah abandoned India for the Australian outback. With her passion for architecture and design, Princess Esra was determined to restore the palaces to their former glory. In 2005 Chowmahalla Palace in Hyderabad was opened to the public. But it is the painstaking restoration of Falaknuma in collaboration with the Taj Group has been truly heroic. Under the Princess’s expert guidance and armed with her collection of photographs of how the palace looked early last century, Falaknuma is magnificent once more. And you don’t have to be a viceroy to stay there.

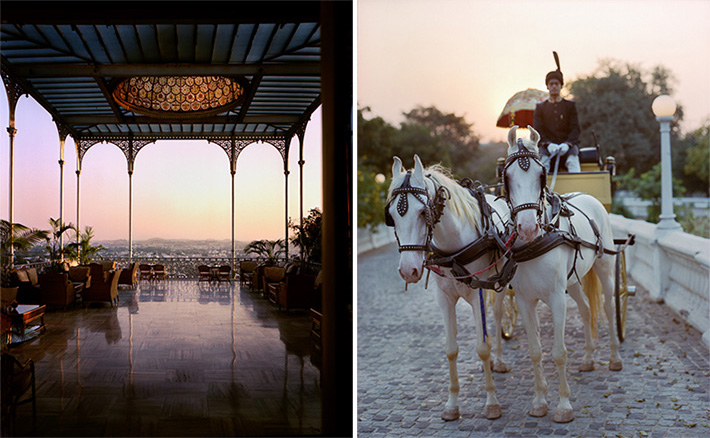

From below, it’s not so prepossessing. We catch only a glimpse of the walls as we’re driven up a dusty road from the streets of the city and there’s no sense of history yet as we’re asked to disembark at the Clock Gate and have our luggage x-rayed. But this is the point where we have to snap our fingers and give ourselves over to history and romance. On the other side of the gate a pretty canopied carriage, drawn by two frisky white stallions, awaits. The moment we’re safely in the buggy, we set off a canter back to the 19th Century.

After a short trot up a winding cobblestone road, past the swimming pool set in a Japanese garden, the breathtaking Coronation Hall with its many pearly turrets and a croquet lawn edged with gates brought from Rajisthan, the horses come to a precise halt at the painted dot where the Nizam’s carriages always stopped. The colonnaded building, painted several times to get the exact pearl grey Princess Esra demanded, sits atop a hill with 360 degree views over Hyderabad. The terrace spills down to a vast lawn that held 35,000 people recently for a party but today is deserted except for a couple of sashaying peacocks.

We are greeted with iced tea and showered with rose petals as we walk upstairs to the entrance lobby, where we’re garlanded with tuberoses as is the custom. Historian Prabhakar says the entrance vestibule was created to give the impression that you are entering the portals of heaven. A marble fountain, topped by cherubs, represents the moon. Exquisite frescoes by Jean Gaudier cover the ceiling and walls, depicting the heavens, with ‘celestial ladies’ floating about the cornices. At the far end of the palace, through the long central courtyard, another fountain is a mirror of this one.

Falaknuma was built in the shape of a scorpion, with the east and west wings forming the ‘pincers’ on the front and the ‘Dome’ terrace between the hotel’s two restaurants, as the tail. Legend has it that the scorpion shape meant the building was cursed. Certainly Sixth Nizam Mahboob drunk himself to death at an early age and his heirs didn’t fare much better. But, despite a kind of Victorian stuffiness to some of the formal public rooms that have been kept exactly as they were – the Nizam’s office and the children’s governess’s study for example – most of Falaknuma, with its beautiful gardens, cool terraces and sparkling fountains, seems enchanted rather than cursed.

‘SIXTH NIZAM MAHOOB DRUNK HIMSELF TO DEATH AT AN EARLY AGE AND HIS HEIRS DIDN’T FARE MUCH BETTER’

Each day the historian Prabhakar takes interested guests on a tour of the rooms in the main palace. He knows the provenance of each and every statue, artwork and piece of furniture. The carpets, he says, have been dyed 300 times to get the New Zealand wool to the same rich red colour the carpets were in the Sixth Nizam’s day. He takes the tour through the Nizam’s library, where the Jacob diamond once sat on the desk, the children’s school rooms and their bedroom, pointing out a wardrobe with a mother of pearl, ivory and lacquer Tree of Life motif that he says is the most valuable piece in the palace. Mahboob’s two sons, Azam and Moazzam, stare smugly from photographs. Growing up to be playboys, gamblers and general wastrels, they weren’t so smug when Mahboob overlooked them and gave the crown to his grandson.

Prabhakar considers the library to be ‘the most beautiful royal library in the world.’ Almost 6000 books are housed in floor-to-ceiling bookcases under a vaulted ceiling, the marquetry adorned with the initials of Falaknuma’s first owner. The collection includes a first edition of Loss of the SS Titanic by a survivor of the tragedy and a complete set of the Encyclopaedia Brittanica donated by King George V when he stayed there in 1906. Off the library lies the ladies’ sitting room, with its silk gossip sofa and mirrored shelves for makeup. The Begum’s bedroom features a wardrobe and bed head constructed in the shape of the front of the palace and a bath with a shower stall made of pipes that released steam scented with perfume.

The two main floors of the palace are connected by an extraordinary suspension staircase constructed in a cantilever system so that each step is made from one enormous single slab of Italian marble. As you trudge up it, portraits of British viceroys eye you critically. Nine statues of the Greek goddesses of learning emerge from the banister. At the top of the stairs oil portraits of the original owner and his family, framed in heavy gilt, are hung beneath stained glass windows depicting British kings and knights. The leadlights and the ceiling light fittings are 24 carat gold.

The first floor lobby leads into the Durbar Hall, where the Eighth Nizam was crowned. The parquetry floor is made of rosewood and teak and the rich curtains come from Italy. The huge Belgian chandelier was completely intact and just needed cleaning. It’s used as a ballroom these days. On the other side of the lobby is the Smoking Lounge with an original Turkish hookah (although the pure gold threads that wrapped around its cords have disappeared.) This leads into the Billiard Room, panelled in embossed leather and beaten copper sheet, dominated by an enormous billiard table by Burroughs and Watts of London, one of only two in the world (the other is at Buckingham Palace.) The furniture in these rich, dark rooms is mostly embossed camel skin, sourced from Turkey. The silk tassels and swags in these rooms would cost a small modern fortune alone.

The dining room with its 101 seat, 32-legged table, has been restored. The Nizam’s chair, set three inches higher than his guests is still at the head. The acoustics in the room are so remarkable that the Nizam could hear clearly conversations at the other end of the room. Each place would be set with a solid gold platter – Mahboob liked to boast that the King of England only had 50 gold platters, whereas he had 101.

Falaknuma’s grandest and most beautiful room is the Jade Room, which was used as the state reception hall and these days opens up to a colonnaded terrace where breakfast is served in the cooler months. It combines Oriental and Art Nouveau/Secessionist influences in the most exquisite way, with the celestial shapes painted in pastels and gold on the ceiling mirroring the shapes set in the rosewood and teak parquetry on the floors. The furniture is Chinese, covered in pale green silk and the room is full of cabinets containing treasures made from porcelain and carved ivory. Extraordinarily beautiful sideboards contain pictures of maidens representing the four seasons. Even the crystal casings on the ceiling fans are unique to Falaknuma.

Our suite is in the old zenana, or harem, with windows opening on to a central courtyard and a fountain set in a star shape that splashes soothingly all night. Designed by a cousin of the princess, Miss Ruya Moccan, the guest room interiors feature furnishings sourced from Turkey, fine pale carpets and walls hand painted by a team of Rajisthani craftsmen. The bathrooms, all black marble and bevelled mirrors, are enormous and opulent. No one knows how many women were housed in the zenana, but it’s fair to say it was more than one hundred, predominantly dancing girls and the daughters of noblemen gifted to the Nizam. Most girls spent one night with the Nizam before being banished to the zenana, never to be called on again, unless she was fortunate enough to bear a son and earn an apartment of her own. It can’t have been a happy place.

In the mornings we are woken by the stirring sounds of the Call to Prayer. There are more than two hundred mosques in Hyderabad and Falaknuma, sitting 2000 feet above the city, captures the sounds and smells of it all. A smoky-rose scent, so beautiful you want to bottle it, rises up with the heat and mingles with the voices of different muezzin, some of them delicate and lyrical, others strident, aggressive. Our suite opens on to a terrace with views right to the distant Charminar, or city gate, where market stalls are heaped with dazzling bangles studded with coloured glass. My favourite parts of the day are the peach-coloured dawn and dusk when the sensory impact of scented air, chanting voices and polychromatic sky touches the soul in the most potent way.

I suppose Falaknuma might be too much like a museum for some people’s tastes. While it has every luxury of a modern hotel, including the full-service Jiva spa, fitness centre, a gorgeous pool in landscaped gardens and a truly marvellous Indian restaurant, Adaa, where the biryani is as celestial as the setting, the public rooms in the palace make no concession to guests who are looking for bars or night life. A group of qawali singers entertain each night before dinner on the Gol Bungalow terrace in the scorpion’s ‘tail’, under the stained glass dome that was brought to Falaknuma from Delhi in 1906. At 4 o’clock in the afternoons, Mohammed Aslam Khan, a world-acclaimed sarangi player, can be found sitting cross-legged in an alcove, plucking strings on the instrument and making beautiful music. You can wander through the restored rooms without running into a soul – except, perhaps, an overly-attentive butler. It’s all very dreamy – a rare and exceptional experience, as befits a palace floating between heaven and earth.

I stayed at the Taj Falaknuma in February. It was amazing. The horse and carriage experience and the rose petals on arrival were divine. I was on a Tasting India tour with Christine Manfield. I’m in love with India.

Your Facebook page is terrific.

I like what you guys are usually up too. This sort of clever work and coverage! Keep up the wonderful works guys I’ve added you guys to my personal blogroll.

I have been checking out some of your posts and it’s pretty nice stuff. I will surely bookmark your blog.

I love your web site. The way it’s laid out, the content and the design. You’ve done a great job. Hope the world gets to see it soon

Hello, it really interesting, thanks http://www.mrandmrsamos.com

[…] this Monday morning… enjoy a few excerpts from FALAKNUMA: AN INDIAN PALACE IS […]